Is there a way back?

EU membership and the Schengen Agreement are all very well - but often it would take just a few hundred metres of tarmac or a couple of kilometres of railway track to bring together towns that fell on different sides of Hungary's post-Trianon borders.

The Trianon Peace Treaty refers to the Ronyva, a small stream in Zemplen, as a navigable river. This stream, which is just a trickle of water in summer, was important because major railway lines ran through the outskirts of Satoraljujhely, the capital of the former Zemplen County. The treaty's authors wanted to take these away from Hungary, so they exaggerated the scale of the Ronyva to make it look like a natural frontier. If the railway junction had been just 100m closer to the centre of the town, then Satoraljaujhely would probably have ended up in another country.

Satoraljaujhely lost out when the new frontiers were drawn up because it lost most of the county it had once dominated. The town ended up at the bottom of a blind ally, but retained the oversized institutions of a county town, but of these, only the prison still retained any use. To this day, it is the prison for the country's most dangerous prisoners. Over the decades since the treaty, locals have had varying degrees of success in maintaining their links to their relatives on the other side of the border, or taking advantage of Slovakia's lower prices.

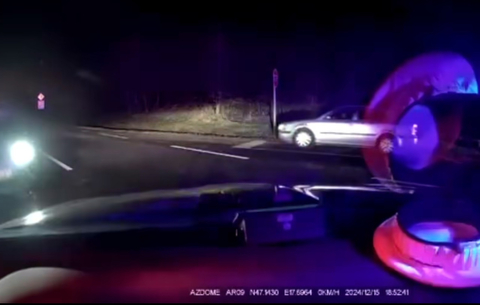

Jan Kalinic, mayor of Kisujhely, a suburb that ended up on the other side of the border, does not speak Hungarian, but he looks eagerly to the day when the border will vanish entirely. He wants to see a bypass built linking Satoraljaujhely and Kisujhely (Slovenske Noe Mesto in Slovak), in order to get the lorries off the narrow city streets. The two sides are drawing up plans and hope to win EU money for their project. The mayor wants the barriers at the border to come down, since this will, for example, make it easier for children to perform at festivals in neighbouring cities, or to go to school on the other side of the border. At the moment, they need a passport and an adult to accompany them. The divided city is linked by two border crossings. One is a long way outside the city. The other is reminiscent of divided Berlin. The border crossing lies at the end of Ferenc Rakoczi II utca, on the far side of the Ronyva. The same street continues on the Slovak side. Once, cars could cross at this point. Later, there was no border crossing at all. Currently, the crossing is open from 6am to 10pm, but only to pedestrians.

Many come to work in Hungary from the Slovakian side, though few go in the opposite direction. They work in factories sewing clothes, or at the metal foundry in the town. Many come to study in Ujhely, Sarospatak, Miskolc or Budapest, but the area's thermal baths, cinemas and discos are also popular. Natalia Frakno, who comes from a nearby village in Slovakia, is studying to be a nurse, and a young man is waiting for her on the Hungarian side. Couples like these tend to hold the wedding in Slovakia, according to Natalia, "because it's much cheaper there." Slovaks tend to come for more exciting shopping - Tesco in Ujhely even accepts Slovak crowns. Hungarians, on the other hand, tend to cross to Slovakia for cheaper beer.

According to Peter Szamosvolgyi, mayor of Satoraljauhjhely, everyone is eager to see the border come down, but there are some anomalies. Recently, the neighbours suggested it would be good if the city border crossing could stay open 24 hours a day, but while the Hungarian authorities agreed, Slovak officials refused. Despite these problems, the two suburbs on either side of the Ronyva tend to cooperate closely. They recently worked jointly on a water main, each using separate sources of funding, which linked up five villages on both sides of the border. The cities have carried out a joint disaster response exercise, and they have helped each other out. When Satoraljaujhely was closed off by snow, Kisujhely sent its snowploughs. The two city councils have sat in joint session, and the cities celebrate 1 May together. The media plays its part. Uhely's RAdio Akiv broadcasts the news in Slovak once a day, and Zemplen TV also broadcasts in the neighbouring country's language.

Borsi, the village where Ferenc Rakoczi II was born, is situated three kilometres in to Slovak territory. Janos Bisztranszky, the mayor, told HVG that he had high hopes for the village's thermal springs, which were recently put to work heating the school. They hope to construct a thermal bath to tempt locals who have tended to bathe in Sarospatak, but they hope to attract Hungarians over as well. Several have been looking to buy houses, and one Hungarian recently moved there from Ujhely, returning each day to work. The closest city in Slovakia is 30km away, and Bisztranszky would prefer it if firemen and ambulances came form Ujhely.

Daily cross-border contacts are just as common in the south east. A businessmen from Sarkad loads his fresh pastries into his van early in the morning and takes them to Nagyszalonta, 20km away in Romania. He has seen a young man from Battony apply for work in a paint shop in Arad. Though they agreed on wages, the Romanian owner was not prepared to pay his bus fare. Ties are strengthening in Nagylak, which was also torn apart by Trianon. This town by the Maros is also called Szelmenc II, since Trianon divided the primarily Slovak-speaking town between Hungary and Romania.

Ciceac Vasile, mayor of the Romanian part of Nagylak (Nadlac in Romanian), told HVG that he has daily contact with his counterpart on the Hungarian side, because they want to work jointly on developing the water main and the sewage system. Recently, a Hungarian company acquired a site in the Romanian city, where the company will build a biodiesel plant. The company is recruiting on both sides of the border. To strengthen ties still further, it would help if the Szeged-Arad railway line, which was cut in two by Trianon, could be rebuild, but there is little hope of this happening, even though only 3km of track would need to be repaired. Still, the rebuilding of the bridge across the Danube in Esztergom and the border crossing at Ipoly shows that restoring transport links pays dividends. Nonetheless, plenty of railway lines remain closed, including the line linking Miskolc and Kosice.

In the west, the first joy of rediscovery has faded. Nothing in Pinkamindszent suggests that Austria is nearby, even though the village is just 1.5km away from Nagysaroslak (Moschendorf in Austrian) in south Burgenland. The road out of the village runs only to the national frontier, and then comes a 500m gap until the road restarts on the other side. To cross, locals have to travel 5km. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, both city councils wanted to open a border crossing, but the citizens of Moschendorf voted against the proposal in a local referendum. They worried about the tranquility of their environment, it was said.

The linguistic boundary between the two villages became a national frontier in 1921, but ties only snapped with the building of the Iron Curtain in 1948. Most of the vineyards and wine cellars ended up on the Austrian side. The village had 829 inhabitants in 1900. Now there are only 156. The closure of a railway line in 1960 drove many inhabitants away.

This frontier also divided families. Take the Csizars. The mayor's cousins live on the other side. Even in the past, it was possible to get a priority visa to attend a funeral, and relatives visited each other more frequently when the trip was exciting in itself. "Being Hungarian is not exciting over there any more," says Istvan Csiszar. One Austrian does live in Pinkamindszent, but he came from Vienna and is building himself a weekend house.

There was more enthusiasm back in 1989. When the first temporary border crossing was opened, 70 cars crossed over from Austria. Back then, 30 people in Moschendorf started learning Hungarian, but language classes, which tended to turn into drinking sessions, slowly came to an end.

JÁNOS IRHÁZI,ERIKA PÁLMAI, LÁSZLÓ PUSZTAI