Not a life-and-death issue

The former Hungarian-Soviet Oil Company (Maszolaj) is being taken away from us. Once again, and now the Austrians are the villains - the Austrian government owns 31.5 per cent of OMV, which has been buying up Mol shares. It's no longer about war reparations, of course. This time they're paying - but we're not pleased. Actually - who, exactly, is not pleased? Shareholders seem to be happy, at any rate. They're more than willing to sell.

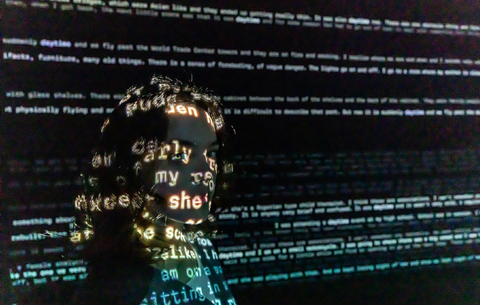

© Túry Gergely |

If we type "hostile takeover" into a search engines, we will find no shortage of reports stating that a hostile takeover is hostile only towards a company's management. Normally, the reason for the attack is the company's lack of efficiency or the undervaluation of its shares. Management has an interest in beating back a hostile takeover, and they are also strongly motivated to spread the word that the matter is just important to employees, to customers and even to the country. But research has shown that none of this is ture. Generally, for example, hostile takeovers tend not to lead to lay-offs. It's not just Hungarian governments that fall for this trick. There are plenty of west European examples. Spain's government recent defended the energy provider Endesa from Germany's E.On. Plenty of US states have erected extraordinary legal barriers against hostile takeovers.

If they are allowed to, then so are we, surely? We are, but why bother?

© Müller Judit |

There's a more abstract approach, as well. Look at Mol's national high-pressure gas distribution network. Is it right for such a network to be in private hands? There's more debate about this now than back at the time of privatisation. There are arguments to be had, but it's also worth asking what private property actually is. I, for example, am the "owner" of a house in a village. Yet I can't change its facade, and I'm obliged to cut the grass in the garden. The state has enormous regulatory power, and despite all the right- and left-wing populism we are treated to, the state has the same power when it comes to big multinational companies.

KÁROLY ATTILA SOÓS

The author is an economist.