Right-Wing Extremism: Back by Popular Demand

While the far-right is indeed ascendant in several Eastern European countries, its threat is decreasing in Western Europe. That’s the conclusion of the Political Capital Institute’s Demand for Right-Wing Extremism (DEREX) Index.

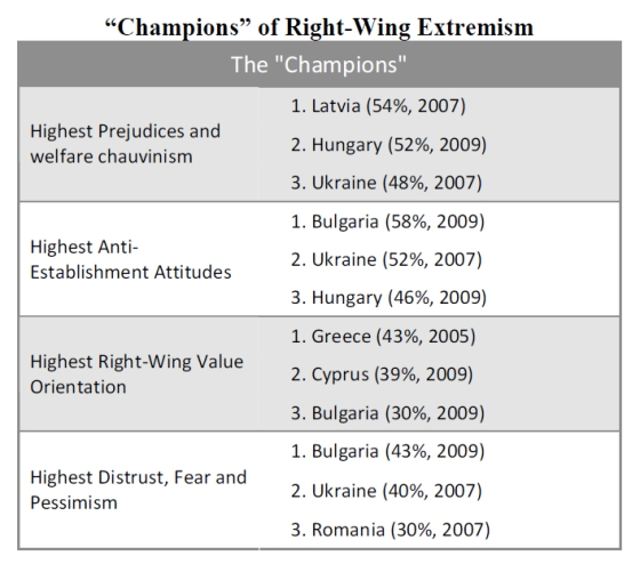

The extreme-right wing is in demand – at least in Eastern Europe. That’s the conclusion of the Political Capital Institute’s Demand for Right-Wing Extremism (DEREX) Index, which measures and compares people’s predisposition to far right-wing politics in 32 countries using data from the European Social Survey. Turkey, Ukraine, Bulgaria and Hungary show the strongest demand for discriminatory, anti-establishment and authoritarian ideologies.

In Hungary, the number of potential right-wing extremists more than doubled from 10 percent in 2003 to 21 percent in 2009. In this regard, Hungary is the exception that disproves the rule: Political Capital’s study rebuts the oft-cited notion that the far right-wing’s social base has been expanding across Europe in recent years. While the far-right is indeed ascendant in several Eastern European countries, its threat is decreasing in Western Europe.

This is partly because in Western Europe, the extreme-right’s main appeal lies in its anti-immigration policies, a subject that rarely leads people to reject the political establishment as a whole. In Eastern Europe, prejudice and anti-Gypsy attitudes are closely linked to opposition to the political system, distrust and general malaise. This combination can pose a major threat to stability.

German sociologist Ralf Dahrendorf said it takes six months to replace a political system, six years to transform an economic system, and 60 years to change a society. Dahrendorf’s maxim takes on new meaning when we examine how people’s relationships with their democratic institutions can be transformed in the space of just a few years. The number of Ukrainians who expressed antagonism toward the political establishment skyrocketed from 25 to 51 percent during the two years following the 2005 Orange Revolution – a time when many Ukrainians felt their new leaders had let them down.

In Hungary, the proportion of people who were angry with the establishment nearly quadrupled from 12 to 46 percent between 2003 and 2009. This kind of quick, radical shift is not unique to Eastern European countries: Experiences such as wars, terrorist attacks, economic crises or extreme dissatisfaction with the government can quickly reshape a nation’s values, even when those values are firmly embedded in the culture. Such principles include tolerance of minorities, trust in fellow citizens and trust in social institutions.

The DEREX Index makes it possible to track changes in social phenomena that threaten to radicalize a society. High demand for right-wing extremism poses broad array of risks for governments: Low levels of trust can render the democratic system unable to function. Anti-elitism and economic protectionism can destroy the investment climate. Xenophobia and aggressive nationalism can endanger both domestic and regional peace.

A prejudicial, nationalist and anti-establishment public can push political leaders toward greater radicalism. A good example is Bulgaria, where Prime Minister Boyko Borisov’s government frequently steps outside democratic boundaries to try to settle scores with opponents. The government’s law-and-order rhetoric, if put into practice, would make Bulgaria look more like a police state than a democracy. However, it meets with widespread public approval.

The danger is most prominent in Europe’s eastern half. Potential extreme right-wing supporters are most numerous in countries that have recently gone through tumultuous periods, such as Ukraine, Hungary and Bulgaria. Far-right sympathies also run high in Israel and Turkey. The index shows that 20 to 30 percent of these countries’ populations are predisposed to right-wing extremism.

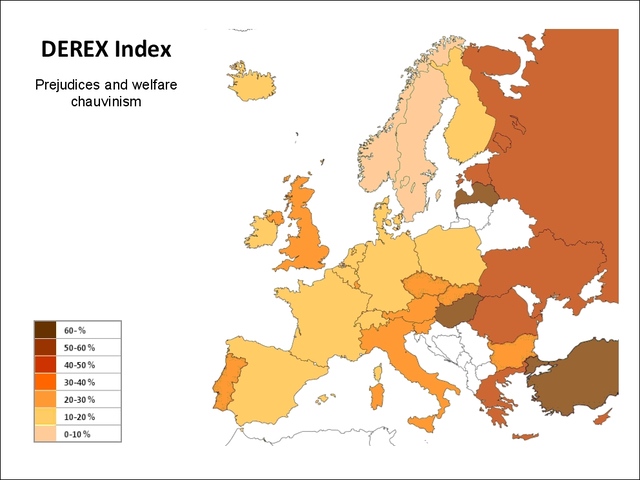

Although it may seem that demand for far-right wing politics divides itself along East-West lines, there is also a North-South divide. Southern members of the EU-15 such as Greece, Italy and Portugal have high rates of demand compared to, say, Scandinavia, where barely 1 or 2 percent of the population express sympathy for such ideas. Portugal is the only Western European country where demand for right-wing extremism has grown significantly in the past six years; Great Britain registered a smaller increase. In other Western European countries, demand for right-wing extremism has been waning, according to the index.

This runs contrary to conventional wisdom: People may think the far right has been gaining ground because certain components of extremism have strengthened in certain countries – for example, prejudice has risen in Austria. In addition, right-wing groups such as the Dutch Party for Freedom have chalked up successes at the ballot box. However, the overall social base for right-wing extremism has been shrinking in the West, along with its inherent political risks.

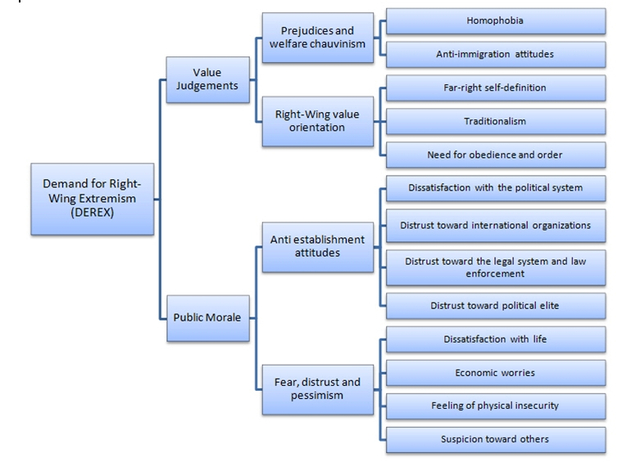

Like far right-wing parties, demand for far-right extremism is a many-headed beast that takes different forms in different countries and regions. Former U.S. Health Secretary John W. Gardner, a Republican in U.S. President Lyndon Johnson’s Democratic administration, once quipped, “Political extremism involves two prime ingredients: an excessively simple diagnosis of the world's ills, and a conviction that there are identifiable villains back of it all.” Gardner’s two ingredients highlight two different approaches to extreme-right politics: The “simple diagnosis” ingredient corresponds to DEREX’s “Public Morale” index, which measures people’s relationship with their country’s political and social institutions, their leaders and their fellow citizens, as well as their views on politics and the economy. The higher a country’s score, the lower its public morale. The “identifiable villains” ingredient corresponds to DEREX’s “Value Judgments” index, which probes people’s attitudes towards outsiders and minority groups (homosexuals and immigrants), conformity to social norms, religiosity, and obedience to authority.

In most Eastern European countries, (low) public morale plays a far greater role in people’s extreme right-wing proclivities than the people’s value judgments. This speaks volumes about the shape Eastern Europe is in 20 years after the fall of communism. East Europe’s far right makes political hay from dissatisfaction with the political system, the government and the general state of affairs. (This is increasingly true in Bulgaria and Ukraine.) In most Western European countries (except Portugal), the opposite is true – value judgments play a much bigger role. Western Europe’s (neo)populist radical parties usually build their political fortunes on opposition to globalization and demand for authoritarianism, traditionalist chauvinism, and ethnic nationalism.

Although Western Europeans’ rates of prejudice and xenophobia are more significant than their anti-establishment attitudes, their Eastern European brethren run rings around them in both departments. Paradoxically, opposition to immigration is strongest in countries that have the fewest immigrants. “Virtual” foreigners are apparently capable of generating just as much fear and aversion as the tangible ones.

Western Europe’s low levels of prejudice may be somewhat misleading. Geert Wilders, the Dutch politician charged with hate speech against Muslims, was probably right when he said, “I say what the majority thinks, but does not dare to say.” Western Europeans feel a strong pressure to be “politically correct;” tolerance is frequently part of school curriculum. Some respondents are therefore probably reluctant to express prejudice toward minorities in front of others, including the European Social Survey’s pollsters. Eastern Europeans, on the other hand, are more likely to treat pollsters to a blunt, unvarnished stream of truth-telling. This is a mark of societal development in the West: Hidden prejudice rarely leads to openly discriminatory behavior – at least not on a conscious level.

Right-wing extremism not only poses a threat to the majority, but to minorities as well. Minority groups that experience discrimination at the hands of radicals usually become radicalized themselves. For example, 20 percent of Bulgarians belong to the country’s Islamic minority, and roughly 16 percent of these are potential extremists, according to DEREX research. This means 4 percent of Bulgarians are potential Muslim extremists. In other words, Bulgaria’s ethnic Turkish minority is at risk of radicalization, not just the Slavic majority that may harbor anti-Turkish or anti-Gypsy sentiments.

International conflicts usually cause the social base for extreme right-wing politics to expand. Typically, certain groups within a country feel the need to be “battle ready” at all times, and not just in Europe – the phenomenon can be seen in Israel, Greece, Turkey and Cyprus. These societies are characterized by extremely high prejudice (especially against immigrants), a strong value for authoritarianism and obedience, and robust right-wing traditionalism.

However, these values do not translate into a desire to break with the political system or institutions. Public morale in these countries is generally strong; the far-right wing’s main targets are not political institutions, but “outsiders” – peripheral and minority groups. This kind of outlook is primarily the result of a high level of social conflict – the threat of war or terrorist attacks, or antagonism on the diplomatic level. The cases of Israel and Cyprus need no explanation.

To illustrate: Both Turks and Greeks felt antagonized by the conflict between their ethnic cousins in Cyprus. Tensions were running especially high in 2005, the most recent year for which data is available for both countries. Cyprus’ Greek majority had just rejected the United Nations-sponsored peace plan in a 2004 referendum (See HVG, Nov. 29, 2004). The inimical atmosphere probably stoked the coals of Greece’s name dispute with Macedonia. Meanwhile, Turkey was mired in a chaotic state of near-war with neighboring Iraq: Numerous Turks had fallen victim to Iraqi extremists and Ankara feared that Iraq’s newly liberated Kurds would stir up pro-independence sentiments among its own Kurdish population.

Only one Eastern European country fell into this pattern of hostility. Slovakia’s Value Judgments index, meaning prejudice and right-wing values, rose between 2005 and 2009, while the Public Morale index improved markedly. Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico’s government apparently buoyed public opinion with its mix of nationalism and militant protectionism. This was helped by the fact that a large swathe of the population was pleased with Fico’s economic performance, as well as his symbolic victories in promoting a “new Slovak identity.”

Demand for right-wing extremism in the neighboring Czech Republic rose between 2003 and 2005, the most recent year for which data is available. This is primarily down to deteriorating public morale: One of the country’s least popular and least successful left-wing governments took power in 2003.

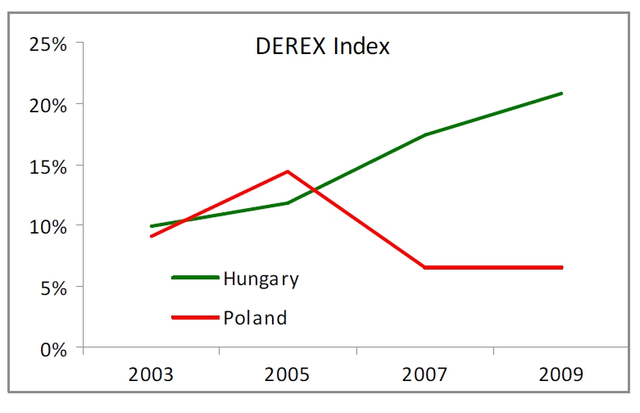

A comparison of Poland and Hungary may make for some depressing reading for Hungarians. The two countries started at about the same base in 2003: 10 percent of Hungarians and 9 percent of Poles were potential supporters of the extreme right. By 2009, Poland’s DEREX score had dropped by nearly a third and Hungary’s had doubled.

Poland’s DEREX ranking peaked in 2005, the year its left wing government disintegrated amid corruption scandals and was replaced by an alliance of right-wing fundamentalist parties led by the Kaczinsky twins. Fulminating anger toward the governing elite drove the index upwards between 2003 and 2005, even as public opinion among the traditionally conservative and religious Poles moved only slightly rightwards. Yet since 2005, the percentage of Poles who support extreme right-wing policies has been on a downward trend.

The biggest difference was the improvement in public morale: After 2005, public opinion was “consolidated.” The anti-elite trend began to turn around and people began to feel more positive about the economy. Poland is a good example of how demand for right-wing extremism can be swayed by the success or failure of middle-of-the-road parties, along with changes in consumer confidence.

Meanwhile, Hungarians’ predisposition to far-right ideas has been on an uninterrupted incline since 2003. Growth in prejudice – especially anti-foreigner sentiment – has been a major contributor, shooting up from 37 percent of respondents in 2003 to 55 percent in 2007. More importantly, public morale deteriorated, driven by anger towards politicians and mounting dissatisfaction with the government and the democratic system itself. In Hungary’s case, distrust has extended to all institutions, including those that only play a minor role in Hungarian public life. For example, the number of people who said they distrust the U.N. nearly tripled from 5 percent to 15 percent between 2003 and 2009. U.S. Health Secretary Gardner’s observation on extremists’ penchant for “simple diagnoses" rings especially true here: Hungary’s extreme right wing is creating a popular ideology out of “everything and everyone is bad.”

Supply Side

Societal demand for right-wing extremism does not automatically create a supply of right-wing extremists. Consequently, countries with high DEREX scores do not necessarily have strong far-right parties and movements, and countries with large radical-right movements do not necessarily score highly on the index (although these phenomena generally do go hand in hand). There are two reasons for this: On the one hand, Political Capital’s indicators measure right-wing extremism’s socio-political risk, not its institutional strength; on the other hand, a country’s supply of extreme right-wing parties is influenced by numerous factors above and beyond popular demand.

The supply side is certainly not independent of the demand side. This is demonstrated by the fact that Western Europe’s extreme-right wingers are usually far less critical of the political system than their staunchly anti-establishment friends in the east. DEREX data indicates that antagonism toward the system is weak among Western Europeans: Their scores in the “anti-establishment attitudes” and “fear, pessimism and distrust” categories are fairly low. There is therefore a clear link between societal demand and political supply in these countries.

In Western Europe, the far-right’s main selling point is its anti-immigration stance, reflecting high numbers in the “prejudice and welfare chauvinism” category. Strong anti-foreigner parties exist in Denmark, the Netherlands and Finland, yet the percentage of votes they receive at election time is generally lower than their scores in the “prejudice” sub-index. Anti-immigration is sometimes packaged together with other proposals, but these hardly ever include a wholesale toppling of the political system. This ensures stability.

By contrast, prejudice and anti-Gypsy sentiments in Eastern Europe are generally linked to strong anti-establishment attitudes, distrust and poor public morale. This is blatantly obvious in the region’s “Guard” phenomenon, where right-wing parties support the formation of paramilitary organizations that openly question the state’s monopoly on violence. Sometimes, these groups practically call for an alternative state organization. Bulgaria’s National Guard organization came first in the summer of 2007, followed by the Hungarian Guard (Magyar Gárda) and the Czech National Guard. No such groups have ever cropped up in any Western European country (except Italy). The west’s extreme right-wing groups therefore do not threaten democratic stability, while Eastern Europe’s democracies look decidedly less stable.

In this context, it is all the more worrisome that Eastern Europe’s extreme right-wing parties are cozying up to Russia, despite their efforts to position themselves as committed anti-communists. This attraction can be explained by their admiration for the Russian political model: Authoritarian, nationalist governance that extends control over strategic economic sectors in the name of the national interest. Many Eastern European right-wing parties view this system as a paragon that is worthy of emulation.

History is the primary (though not decisive) factor in determining the supply of right-wing politics in a given country. The question is not just what role the extreme right played in the past, but whether society has been able to come to terms with it. In this historical context, there are pronounced differences between Western and Eastern Europe. In the west, extreme-right parties began to break with their fascist roots in the 1960s. When these parties began to flourish in the 1980s and 90s, they pursued a kind of neo-nationalist, neo-populist line centered on anti-immigrant and anti-elite policies.

Parties such as France’s Front National, Belgium’s Vlaams Belang (“flemish interest,” formerly Vlaams Blok), the Austrian Freedom Party, Italy’s National Alliance and the Danish People’s Party have more or less severed ties with fascism, an ideology that became widely discredited in Western Europe after people were forced to face their demons from the 1930s and 40s. These parties attract supporters based upon their ability to provide simple answers to serious questions that affect a lot of people. It is no coincidence that the extreme right has the least room for maneuver in Germany, which had the heaviest burden of guilt to process following World War II. The German ultra right thus enjoys the strongest support in the country’s eastern regions, where people have not yet fully confronted this chapter of their history.

The situation is fundamentally different in Europe’s formerly communist countries. Here, it was primarily extreme left-wing ideas that were discredited in the decades after the war. Memories of extreme right-wing dictatorships have grown foggy with time, even more so because people were never forced to come to terms with them. Social classes that are open to extremism in Eastern Europe are therefore more receptive to the extreme right than to the extreme left. The supply of right-wing ideas is also different: Parties brazenly combine elements form pre-1945 fascist movements with ideas from modern neo-populist movements in Western Europe.

Legal restrictions are the second important factor affecting the supply of right-wing politics. A nation’s legal framework and the strength of the political system can either assist or hinder the development of extremist parties and movements. The structure of a country’s electoral system, party-finance restrictions, laws on extremist activities and their enforcement can all make a big difference. Political parties in France and Turkey must pass relatively high vote thresholds to enter parliament, making it difficult for extremist parties to win seats. German and Dutch law prohibits both extremist movements and “hate speech,” and authorities take a vigorous approach to enforcement. By contrast, Italy’s Constitution includes a ban on fascist organizations, but enforcement is lax. Eastern European countries’ regulations on extremism are fairly toothless and authorities lack the capacity to enforce them. For proof, one need look no further than the street violence that broke out in Hungary in autumn 2006.

The structure of a country’s political power base can also affect the development of supply. Who is inclined to enter into an alliance with right-wing extremists, and who is against them? Are there any anti-extremist movements, and how strong are they? What kind of national strategy exists to fight far right-wing groups – do moderate parties team up with the extremists, thereby “taming” them, or do they try to reach out to some of the extremist supporters and bring them into their own camps? Or do the moderates condemn the extremists and distance themselves from the far right?

Cooperation or unification with other parties can spawn internal strife within extreme right-wing parties, as has happened in Austria, Italy and Belgium. Moderate parties also face considerable risk when cooperating with extremists or trying to usurp their voters: If they succeed, the extremists may manage to radicalize them on certain issues.

The moderate “usurpation” strategy has helped stop far right-wingers from gaining ground in recent years, even as the economic crisis created fertile ground for their politics. Poland’s center-right government has managed to keep its popularity throughout the downturn, and many former supporters of extreme right-wing parties have gone over to the opposition Law and Justice (PiS) party. French President Nicolas Sarkozy managed to win over numerous radical-right voters with his rhetoric and his firm-handed policies. The Slovak National Party, which was weakened in connection with corruption scandals, stumbled even further when its supporters began deserting in favor of Prime Minster Robert Fico’s anti-Hungarian, social-populist and authoritarian style of governance. The one place where the strategy failed utterly was Hungary, where the right-wing Fidesz party’s “one camp, one flag” campaign failed to stop the ultra right-wing Jobbik party from gaining support.

Finally, the supply of extreme right-wing politics can be influenced by their organizational skills and the efficiency of their politicking. A party needs sufficient financial resources, a volunteer network, a capacity to influence public opinion, and perhaps most important of all, a charismatic leader. It is impossible to categorize the various countries’ far right-wing organizations in this regard – we can only analyze them on a country-by-country basis. Still, extreme right-wing parties do have some important general characteristics: They are unpredictable, and they have a knack for building up support quickly – and losing it just as quickly.

There is no far-right part in Eastern Europe that has been able to maintain significant approval ratings over the past 20 years. This turbulence in itself represents a risk: Extreme right-wing parties can appear out of nowhere, as happened with the Greater Romania party at the turn of the millennium, the League of Polish Families in 2005 and Hungary’s Jobbik party in the past few years. The DEREX Index shows that societal attitudes can change at an equally hectic pace, providing a social base for savvy political forces to build upon. This presents a serious challenge for Eastern Europe’s young democracies to overcome.

By Attila Juhász, Péter Krekó and Csaba Molnár, Political Capital Institute

English translation by Alex Kuli

Methodology:

Political Capital designed the Demand for Right-Wing Extremism (DEREX) Index using its own theoretical model and data from the European Social Survey, a biannual study that tracks changes in societal attitudes and values in 32 countries. Political Capital’s risk-analysis division developed the model, chose the questions, determined subject groupings and set the criteria over the course of roughly one year. The DEREX study is not in any way related to Political Capital’s former research contract with the Hungarian National Security Office, although analysts naturally used some of the experience they gained while performing research for state authorities. Political Capital also used results from its two-year joint research project on far-right extremism with the Hungarian Anti-Racist Foundation (Overview 2008 and 2009) in developing the index.

DEREX’s data is culled from people’s responses to 29 questions in the European Social Survey’s database beginning in 2003. These questions are divided into four categories: Prejudice and Welfare Chauvinism, Anti-Establishment Attitudes, Right-Wing Value Orientation, and Fear, Distrust and Pessimism. These sub-indices are then grouped into two larger categories: Value Judgments, which combines prejudice/welfare chauvinism with right-wing value orientation, and Public Morale, comprising anti-establishment attitudes and fear, distrust and pessimism.

Each of the four sub-indices has a numerical value that shows the rate of people over the age of 15 whose answers indicate that they belong in that category. A country’s DEREX number is determined by the number of people who belong to at least three of the four categories – for example, respondents who express anti-immigrant sentiments, anti-establishment attitudes and right-wing values all at once. Using these strict criteria, the DEREX Index examines the percentage of people whose extremist views could destabilize a country’s political and economic system – if these views continue to gain credence.

Source of Data:

ESS Round 1-4: (2002-2008.) Norwegian Social Science Data Services, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data.