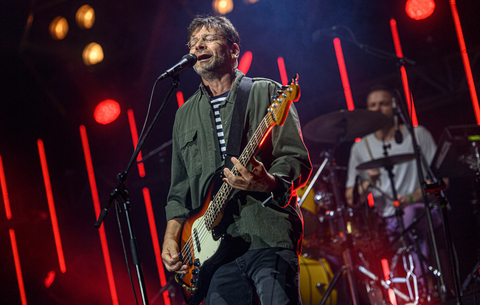

Albert Takács

"I was always a good student," says the 52-year-old freshly appointed minister, a constitutional lawyer by training.

© Marton Szilvia |

You are known for your sharp differences of opinion with Laszlo Solyom, the president. You have criticised some of his rulings as president of the constitutional court, while he refused to nominate you for ombudsman recently. People familiar with your disagreements were curious to see what would happen when he handed over your letter of appointment. Was it hard to shake hands?

Not at all. We've known each other since 1969. We worked together at the Legal Institute and we attended Frankfurt University at the same time. We had good personal relations at the time, and I have learned much from his work on civil law.

The president must have had similar thoughts...

I can't speak for him, but I'd be glad if my books or studied received the kind of critical attention I gave his works.

How relaxed?! We were struck by the pictures released of you once the news of your appointment came out. We wonder if your wife asked you to change your style? Or is there a new love in your life?

You're clearly men of the world, because it's true that my family told me my years-old hairstyle was getting tired. In any case, this is my first and only marriage.

But your relationship with the police is new. And they are in constant trouble with civil society organisations. Now the have a boss who at least physically resembles an underground minister of culture. Or maybe your new hairstyle tells us you're taking it all back?

Maybe one day I'll wake up with no desire to comb and wash. But I don't think my physical appearance is that important. The musician Tamas Somlo reminded me recently that he has great hair and even rides a motorbike. Maybe that'll be my next thing: a motorbike. That's my real dream at the moment.

We can hardly wait to see what kind of energies you devote to that. Wasn't it better being an armchair academic with no responsibilities than entering the frontline of politics?

It wasn't easy at the Institute with Tamas Sarkozy and Gyula Eorsi constantly testing our knowledge of civil law and with Andras Sajo checking up on whether we were reading legal theory - but the most recent period of my life was pleasant. We spent the whole day there, morning till night, and we had time to talk. We inspired each other: how could I know the constitution of only 24 countries when my office mate knew 32?

And just look where it took you! How did you get going on your career without being a member of the Party?

I was a member for a while, but only for a year before the regime change. I was there at the party congress where the changes took place in 1989. I just saw a photograph - I'm visible on it.

It's good that you mention it, because somebody will dig it up soon enough. But what led you to join the party at the last minute, just like Janos Martonyi, who is now on the Right.

I wasn't obliged to join, but certain benefits were only accessible if you were a member of that forum. That's when the reform circles began. My most important public role was at that congress when there was a spirited debate over whether the party should stand for a social market economy. Many were outraged, but I pointed out that the first paragraph of the German constitution commits the country to precisely that economic mechanism. I persuaded everybody as well.

You've worked as a lawyer since. Have there been any important, memorable cases?

I took part in some significant trials. The matter at hand was whether you had to pay a supplementary fee if as a tenant you placed an exhibition cabinet on a common wall in a jointly owned block of flats. Of course, I represented my client in the appropriate way, wearing my gown.

You're cautious, then. Beyond that, people say you are always very elegant. How many suits did you try on before your swearing in ceremony?

Lots. You can easily check, because three years ago Elite magazine chose me as one of the country's 10 most elegant men.

But you still buy new clothes?

New dinner jackets, certainly. When I last put it on, it was getting a bit ragged.

At least you were never caught on camera with a hole in your sock like Paul Wolfowitz. That led to his downfall. But you must need to look good in office: as everyone knows, you are often spoken of as a candidate for constitutional court judge, for ombudsman, and now you've been nominated as minister. Let's be honest: what would you have liked best?

I'll admit that I'd most like to have been a constitutional court judge. I like analysing things, sitting down in my office in the morning, and reviewing the facts. I knew in advance that the president wouldn't nominate me as ombudsman, and I was also forewarned about being appointed minister. If they had come at the same time, I'd have had to think about it. But I'm very pleased to be a minister.

ANDRÁS LINDNER - ZOLTÁN HORVÁTH