Historikerstreit

A colonel general who was stripped of his rank following a conviction by a people's court in 1950 is to be reinstated posthumously, the Defence Ministry's Rehabilitation Committee has decided. The defence minister announced that Ferenc Kisbarnaki Farkas would regain his rank after a Supreme Court decision annulling his original conviction. The decision has shone a spotlight on Kisbarnaki Farkas's career, with historians disagreeing over the role he played in the Arrow Cross era.

Kisbarnaki Farkas's rehabilitation has no practical consequences, since the officer died in West Germany in 1980 and none of his close relatives live in Hungary. The gesture has nonetheless proved controversial.

In an interview with the weekly 168 Ora, Krisztian Ungvary described Kisbarnaki Farkas as an official of the fascist regime led by Ferenc Szalasi. He said the general had "ended his military career as the chairman of a military committee that sentenced to death a former brother officer, the general Kalman Hardy, and sentenced others to lengthy prison terms." He continued: "As commanding officer of the sixth army, he had a central role to play in Hungary's October 1944 attempt to leave the axis. Horthy trusted him, ordering him and his troops to Budapest, and informed him of his plans the day before Hungary left the axis. But Farkas sabotaged the plan and swore an oath to Ferenc Szalasi after the attempt had failed. Straightforwardly, he broke his military oath and betrayed the Regent." Ungvary said Kisbarnaki Farkas was "a man who swore an oath to Ferenc Szalasi, the leader of the nation, and who had been promoted to colonel general by mass-murdering Arrow Cross members, and who played a role in the last hours of the Arrow Cross regime, presiding over the trials of 'betrayers of the nation' held at Sopronkohida." Kisbarnaki Farkas had also dispatched the Crown of Hungary and other national treasures to Vienna, he said.

Tamas Kovacs, director of the Holocaust Memorial Centre, holds a similar view of Farkas. Speaking at a conference held at the Institute for Military History, he said the general had been largely responsible for sending to the West some USD3bn in national treasures, including the crown jewels, priceless gold treasures and the collection of national seals. In doing this, he cooperated with Kurt Becher, the German commander. There was, he said, not enough evidence to establish if he had played a direct role in the 'final solution' to the Jewish question. Attila Bonhard, director of the military archives, painted a more nuanced picture of the officer's career. He said Kisbarnaki Farkas, a committed Catholic officer who received a papal award for helping arrange a Eucharistic congress, was more an Anglophile than a German collaborator. He was close to Pal Teleki, and together they set up the Hungarian boy scouts' movement. As commander of the sixth army, based in Debrecen, he worked alongside General Lajos Veres preparing to turn against the Germans on 19 March 1944 as soon as Miklos Horthy gave the order to resist. This never happened - the Regent gave his approval to a continuation of the war.

In July 1944, having replaced General Beregfy, an incompetent but fanatical Arrow Cross member, Farkas beat back a Red Army attack across the Carpathian mountains, employing merciless methods to stem the Hungarian army's retreat. By so doing, he earned the trust of the Germans - but Horthy was also an enthusiast as he planned Hungary's departure from the axis, suggesting him as a member of the Lakatos government. Ahead of 15 October, he ordered him and his troops to Budapest and named him commander of the Pest bridgehead. His role in the Arrow Cross coup is not unambiguous: it is hard to establish whether he deliberately ignored Horthy's 'exit order' or whether his troops had not managed to reach Pest in time.

Farkas was not dismissed after Szalasi came to power: he swore an oath to the Leader of the Nation. Beregfy, now Minister of War, named him Government Commissioner for Evacuation, in charge of 'rescuing' national treasures, and he was at the same time promoted to colonel general. In the final months of the war, he presided over the trial of Generals Lajos Veres and Kalman Hardy. They were not executed - Hardy's death sentence was reduced to a lengthy prison term on appeal.

Kisbarnak Farkas sent long letters of self-justification when he was in Western captivity in summer 1945, but he was nonetheless sentenced to life imprisonment in March 1950. The real reason for the sentence, which was passed in absentia, was that he was for a while active in the West German Hungarian émigré community.

In September 1947, when it was clear that the Communist grab on power could not be stopped, it seemed for a short while that the Western allies would support the establishment of some kind of emigre Hungarian government in exile. The members of the last 'legitimate' parliament of Hungary, which had been elected in May 1939, were summoned to Allotting in Bavaria, but only a few dozen MPs, from the former Imredy party and various warring Arrow Cross factions, attended. They elected Farkas prime minister of the government in exile, but he resigned in 1948, realizing that the group did not enjoy the confidence of the Americans. He then became president of the Hungarian Freedom Movement and a member of the Anti-Bolshevik Front of the Nations. When this organization also expired, he devoted his time to the West German Hungarian scouts' movement. From 1962 until his death, he was a captain of the Seat of the Knights' Order, and continued to draw a comfortable income from his retired generals' pension, which was paid by the German state.

Kisbarnaki Farkas was a Janus-faced officer, according to those who advocated his rehabilitation. They argued that though he came close to committing war crimes and crimes against the people, he was spared by fate, leading even the Western allies to regard him as an acceptable figure for a short while. But other historians say he was a criminal. But nobody expected him to remain a contested figure even into the first decade of the third millennium.

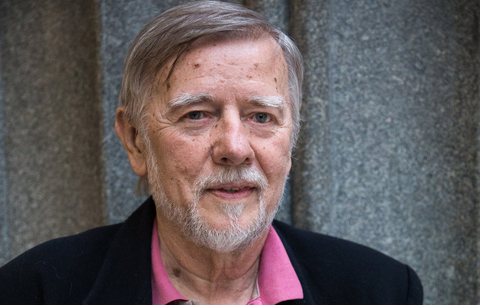

János Pelle